Current Addiction: The Kleptones’ “Uptime/Downtime” double disc

Loaded with diamonds: “Untired,” “Hammer,” Correspondence,” “Welcome Back,” “Hella Touch,” “Care,” “Brightness and Contrast,” “This Song Smells.” Swap the playlists to Downtime/Uptime.

Cinematic/tech artist & filmmaker. Online since 1999.

Current Addiction: The Kleptones’ “Uptime/Downtime” double disc

Loaded with diamonds: “Untired,” “Hammer,” Correspondence,” “Welcome Back,” “Hella Touch,” “Care,” “Brightness and Contrast,” “This Song Smells.” Swap the playlists to Downtime/Uptime.

Underworld’s “Oblivion With Bells” album

“Beautiful Burnout,” “Boy, Boy, Boy,” “Faxed Invitation,” “JAL to Tokyo (Live From Tokyo)”… I believe I’m officially Underworld’s bitch.

“The Remix Game” by Bitter:Sweet

Each track on “The Mating Game” remixed by a different DJ, including Thievery Corporation, Yes King, Solid Doctor and Nicola Conte.

Christopher Hitchens’ God Is Not Great

Christopher Hitchens’ God Is Not Great

[Emphasis from original. Ellipses mine. Page numbers refer to the first edition Twelve Books hardcover.]

These mighty scholars may have written many evil things or many foolish things, and been laughably ignorant of the germ theory of disease or the place of the terrestrial globe in the solar system, let alone the universe, and this is the plain reason why there are no more of them today, and why there will be no more of them tomorrow. Religion spoke its last intelligible or noble or inspiring words a long time ago…. We shall have no more prophets or sages from the ancient quarter, which is why the devotions of today are only the echoing repetitions of yesterday, sometimes ratcheted up to screaming point so as to ward off the terrible emptiness. (7)

As for consolation, since religious people so often insist that faith answers this supposed need, I shall simply say that those who offer false consolation are false friends. In any case, the critics of religion do not simply deny that it has a painkilling effect. Instead, they warn against the placebo and the bottle of colored water. (9)

[Quoting John Stuart Mill:] “He looked upon [religion] as the greatest enemy of morality: first, by setting up factitious excellencies–belief in creeds, devotional feelings, and ceremonies, not connected with the good of human kind–and causing these to be accepted as substitutes for genuine virtue: but above all, by radically vitiating the standard or morals; making it consist in doing the will of a being, on whom it lavishes indeed all the phrases of adulation, but whom in sober truth it depicts as eminently hateful.” (15)

It assures them that god cares for them individually, and claims that the cosmos was created with them specifically in mind. This explains the supercilious expression on the faces of those who practice religion ostentatiously: pray excuse my modesty and humility but I happen to be busy on an errand for god. (74)

In 2004, a soap-opera film about the death of Jesus was produced by an Australian fascist and ham actor named Mel Gibson. (110)

It was not until after the Second World War and the spread of decolonization and human rights that the cry for emancipation was raised again. In response, it was again very forcefully asserted (on American soil, in the second half of the twentieth century) that the discrepant descendants of Noah were not intended by god to be mixed. This barbaric stupidity had real-world consequences…. The entire self-definition of “the South” was that is was white, and Christian. This is exactly what gave Dr. King his moral leverage, because he could outpreach the rednecks. (179)

But to the totalitarian edicts that begin with revelation from absolute authority, and that are enforced by fear, and based on a sin that had been committed long ago, are added regulations that are often immoral and impossible at the same time. The essential principle of totalitarianism is to make laws that are impossible to obey. The resulting tyranny is even more impressive if it can be enforced by a privileged caste or party which is highly zealous in the detection of error. Most of humanity, throughout its history, has dwelt under a form of this stupefying dictatorship, and a large portion of it still does. (212)

In order to be a part of a totalitarian mind-set, it is not necessary to wear a uniform and carry a club or a whip. It is only necessary to wish for your own subjection, and to delight in the subjection of others. What is a totalitarian system if not one where the abject glorification of the perfect leader is matched by the surrender of all privacy and individuality, especially in matters sexual, and in denunciation and punishment–“for their own good”–of those who transgress? The sexual element is probably decisive, in that the dullest mind can grasp what Nathaniel Hawthorne captured in The Scarlet Letter: the deep connection between repression and perversion. (232)

[Quoting Blaise Pascal:] “Le silence éternel de ces espaces infinis m’effraie.”

(“The eternal silence of these infinite spaces makes me afraid.”) (253)

Everybody but the psychopath has this feeling to a greater or lesser extent…. Modern vernacular describes conscience–not too badly–as whatever it is that makes us behave well when nobody is looking. (256)

Paine’s Age of Reason marks almost the first time that frank contempt for organized religion was openly expressed. It had a tremendous worldwide effect. His American friends and contemporaries, partly inspired by him to declare independence from the Hanoverian usurpers and their private Anglican Church, meanwhile achieved an extraordinary and unprecedented thing: the writing of a democratic and republican constitution that made no mention of god and that mentioned religion only when guaranteeing that it would always be separated from the state. Almost all of the American founders died without any priest by their bedside, as also did Paine, who was much pestered in his last hours by religious hooligans who demanded that he accept Christ as his savior. Like David Hume, he declined all such consolation and his memory has outlasted the calumnious rumor that he begged to be reconciled with the church at the end. (The mere fact that such deathbed “repentances” were sought by the godly, let alone subsequently fabricated, speaks volumes about the bad faith of the faith-based.) (268-269)

The study of literature and poetry, both for its own sake and for the eternal ethical questions with which it deals, can now easily depose the scrutiny of sacred texts that have been found to be corrupt and confected. The pursuit of unfettered scientific inquiry, and the availability of new findings to masses of people by easy electronic means, will revolutionize our concept of research and development. Very importantly, the divorce between the sexual life and fear, and the sexual life and disease, and the sexual life and tyranny, can now at last be attempted, on the sole condition that we banish all religions from the discourse. And all this and more is, for the first time in our history, within the reach if not the grasp of everyone. (283)

Current Addiction: Dimitri From Paris’s Cruising Attitude album

Current Addiction: Dimitri From Paris’s Cruising Attitude album

I can’t quite manage to not get happy listening to “Merumo.” Slick, stylish and fun “faux jazz” in the ’60s orchestra style. John Barry on a bender.

Massive Attack’s Heligoland album

Massive Attack’s Heligoland album

Massive Attack is dangerous. Massive Attack is back.

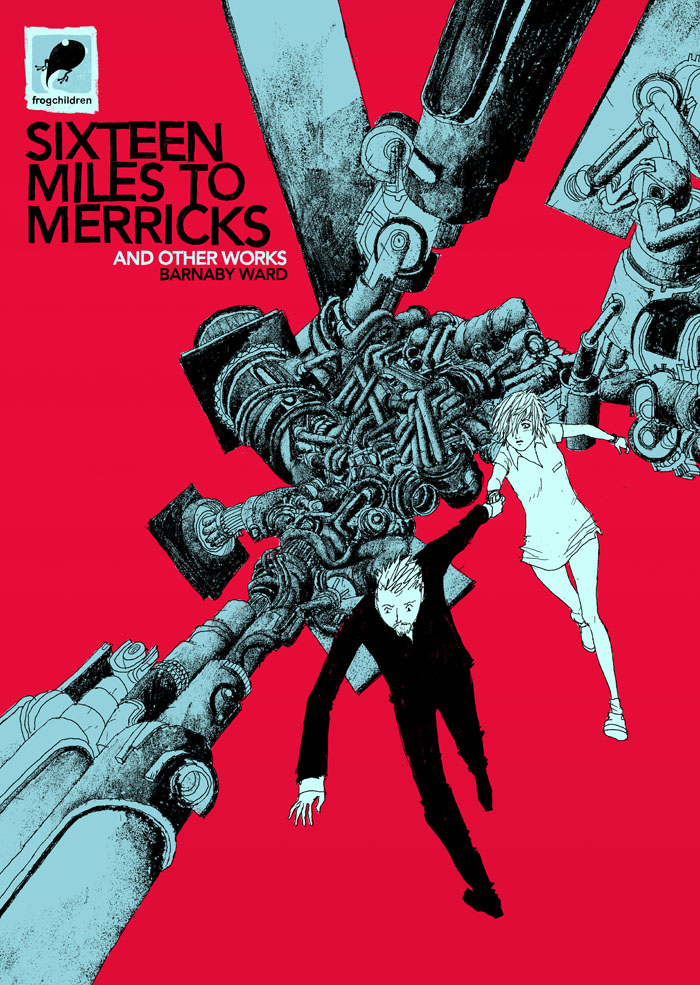

Barnaby Ward’s Sixteen Miles to Merricks and Other Works

Barnaby Ward’s Sixteen Miles to Merricks and Other Works

I’ve mancrushed on Ward before. Picking up his graphic novel was worth the money. Now where’s the next one, Barnaby?

Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth

Does a book listing all non-self-referential books contain itself? A book about the founding of modern logic has no right to be such a compulsive page-turner.

Underworld’s Second Toughest of the Infants album

Velvet smooth electronica with teeth.