Among any number of negative habits is my tendancy to come up with an idea out of desperation at the last minute, play with it for a little while, and then fall in love and want to dump six months into it. Class workshops on different aspects of game design usually trigger this problem. This one is no different. (See also a simple RPG I’m trying to get working in Tabletop Simulator.)

As boring as it sounds, being a lighthouse keeper was as much about lifesaving as shipwreck prevention. A certain solitary type seems to have been attracted to the United States Treasury’s Lighthouse Establishment/Board/Service between 1791 and 1939 (which I think we can agree encompasses the “Golden Age” of lighthouses). Hoisting a dory into four-meter swells from a flooded gear room at the base of the tower in a pitch-black howling gale was a job requirement, and having a sturdy dog with sharp senses and no fear of the water along wasn’t all about companionship. (“Saved,” from the Louis Prang Collection commemorates a real lighthouse dog’s rescue of a child.) Denis Noble’s Lighthouses & Keepers is a good intro to this world.

I’m attracted to the character of an Indian man serving as a keeper sometime around the turn of the last century–someone like WWI US Army Sergeant Bhagat Singh Thind, who under the racial ideas of the time tried and failed to gain US citizenship when the Supreme Court ruled that, while “Aryan” he was not “white.”

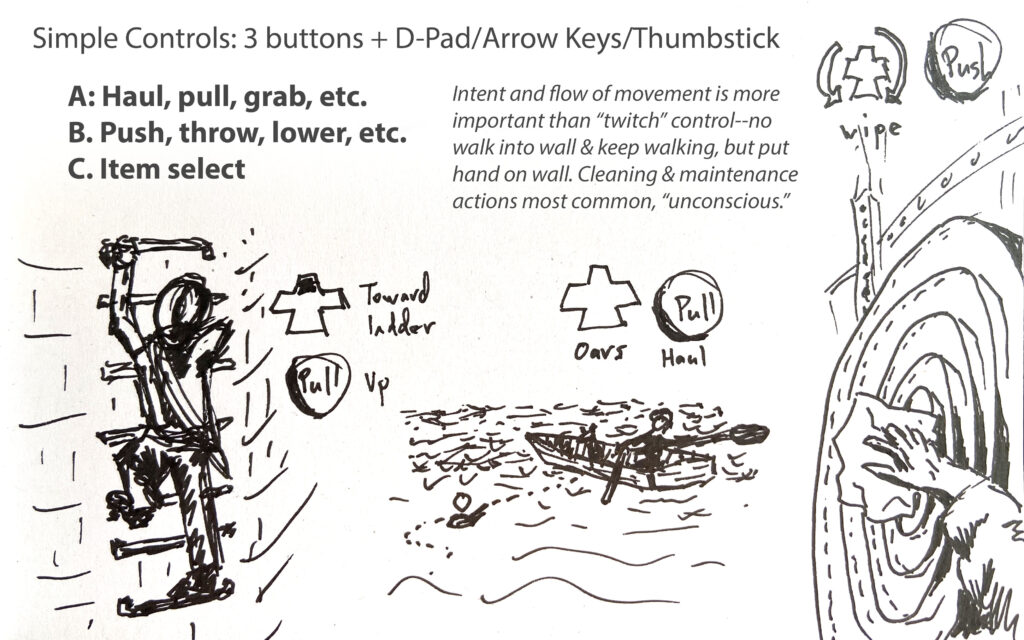

I envision an adventure game made up of episodes (equipment failures, hurricanes, shipwrecks) with free exploration segments before the crisis portion triggers, in which you wander the lighthouse with your dog, read water-damaged books (real ones) about “race science” and other odd but consequential ideas for your character’s situation, and maintain the equipment. The offshore lighthouse serves as a metaphor for your own situation, literally defending a shore you can never reach. In these quiet moments, most of your default push/pull interactions are small acts of cleaning and maintenance (and scritching your dog). I want to make you complicit in the feeling that you’re constantly–even lovingly–maintaining this life-preserving tower.

In truth, an offshore lighthouse was manned by a crew of 3-4. Many keepers were married, and raised families at the facilities. The “solitary” aspect would be a departure from strict historicism–though sickness, injury or just plain poor manpower planning could easily leave a single hand to run a light. It was a quiet and hardworking life, though vastly superior to the sailing trade most keepers left.

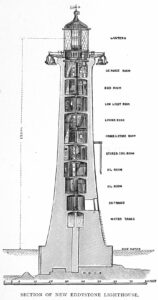

I’ll leave you with this cutaway of Britain’s Eddystone Lighthouse, and an 1892 magazine article describing a visit there. It’s a fun topic to get lost in for a few hours. But for now, I think it’s best I leave it at that.