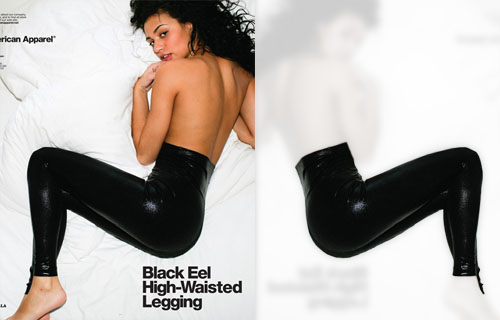

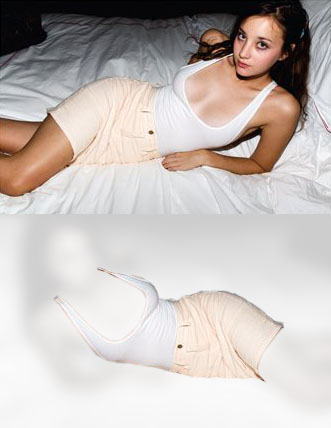

Consider American Apparel. Notice something: The clothing is hideous. Ill-fitting, lumpy, revealing of the wrong aspects of the anatomy, short-changing the best, whoring the remainder. A retro among many retros, that recalls nothing more than a bad Sigourney Weaver movie from the ’80s. You would think that this brand was a failure, a joke.

But you would be wrong.

American Apparel is not a clothing company, but a sprawling meta artwork. The Millenial Era expression of one man’s antisocial personality disorder.

Sex plus product is a trackworn formula. The appeal of the ads goes deeper than that. If the models are appealing but the clothing is unappealing, what does it say if the overall ads are appealing? It says that the models are winning.

Theirs is a temporary victory. An anxious, uncertain victory, as their facial expressions — always their facial expressions, in every ad — beg us to consider. They are winning against the clothing.

They are beautiful. Strangely. Tragically. Momentarily. For just a fleeting instant — so the narrative of the artwork shouts — in the first flush of youth, they are for a manic, over- and underconfident, fast, lost moment precisely Good Enough.

They are prey.

The American Apparel narrative is art, horrible and total. One man’s view of women as objects. Objects to be taken, used, discarded past their shine — much less their usefulness.

Look at this waste. This trash. Stare for a moment. Look what I’ve done to it. What would you like to do to it? Fine, it’s all yours. It’s almost over anyway.

Sartre’s hell can’t hold the man for whom there are no other people.